On 29th October 2018, Lion Air flight JT610 crashed into the Java sea shortly after taking off from Soekarno Hatta Airport in Jakarta, Indonesia. Here’s what we know from the ongoing investigation into the first fatal accident of a Boeing 737 MAX.

How it unfolded

The flight was a scheduled service from Jakarta to Pangkal Pinang. Taking off at 06:20 am local time, it crashed into the sea approximately 13 minutes later, killing all 189 passengers and crew. Of those on board were 2 infants, 10 state officials and 38 civil servants, including 20 finance ministry officials. The crew informed Air Traffic Control that they were in trouble, and would like to return to the departure airport.

Flight 610 never made its turn back to Jakarta. It levelled off at 5,000 feet while the crew clearly tried to rectify the problem on board, before plunging into the sea at a very high speed. Search and rescue teams were dispatched shortly after the flight disappeared from radar screens and floating debris was discovered soon after. It has been reported that one diver has died in the recovery effort.

The Boeing 737 MAX is the latest generation of the hugely popular single aisle jetliner, which has been in airline service since 1968, and over 12,000 have been built. The first 737 MAX prototype flew for the first time on 29th January 2016, entering service in May 2017. There are approximately 220 MAX family aircraft in service. PK-LQP, the Boeing 737 MAX 8 involved in this accident, was delivered to Lion Air in August 2018.

Investigation focus

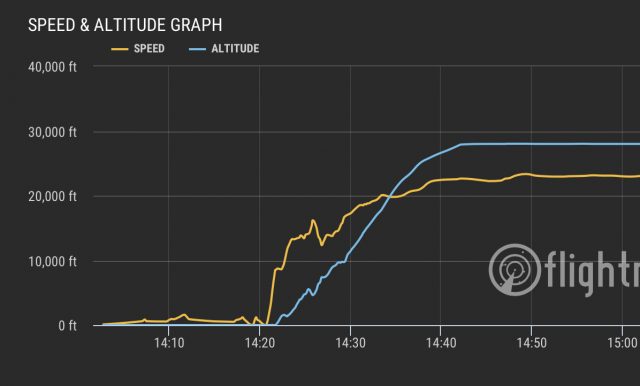

Shortly after the crash, details emerged that the accident aircraft also ran into trouble on its previous flight. Flight JT43 from Denpasar to Jakarta never exceeded 28,000ft, a lower cruise than normal. The flight landed at Jakarta without incident. Early on, the erratic speed data shown from JT43 from Flightradar24 data started to be a focus point for the investigation by Indonesia’s Transportation Safety Committee. Lion Air’s CEO, Edward Sirait, later confirmed that JT43 experienced instrumentation issues, but claimed that the airline fixed the issue.

On 1st November, the first of the aircraft’s two ‘black boxes’ were recovered. The information retrieved from the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) showed erratic speed readings occurred on the previous four flights.

Subsequently, on 7th November, Boeing issued an Operations Manual Bulletin for the 737 MAX family. It warned operators that erroneous readings from the angle of attack (AoA) sensors could trigger the aircraft’s automatic stall recovery. The flight controls of the 737 MAX are designed to initiate a dive when it detects an imminent stall from a high angle of attack situation.

Shortly after Boeing’s safety notice, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of the United States issued an Emergency Airworthiness Directive (EAD) for the Boeing 737 MAX. This further warns of “… potential for repeated nose-down trim commands of the horizontal stabiliser“.

The search for the second black box, the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), continues along with the recovery of the wreckage.

Consequences and context

Australia has banned all government officials and contractors from flying on Lion Air until further notice. In addition, the Indonesian government has ordered that all Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft belonging to Indonesian airlines are grounded for an inspection as a result of the accident. If investigators discover a major design flaw with the 737 MAX, all MAX aircraft could potentially be grounded until Boeing implements a fix.

Indonesian airlines have a typically poor safety record when compared to carriers from other parts of the world. The European Union added all Indonesian carriers to the list of banned airlines in 2007. The EU started to revoke the bans individually from 2009, including low-cost carrier Lion Air, which was lifted in 2016.

Similar accidents

If the results of the investigation prove that issues with the aircraft’s speed and angle-of-attack sensors were to blame, it would add JT610 to the list of other accidents of resulting from faulty instrumentation.

Air France AF447 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean while en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris on 1st June 2009. It took 2 years to recover the black boxes and wreckage, which revealed that ice build up in the speed sensors or ‘pitot tubes’ and lead to faulty speed readings. Believing the aircraft was out of control, the crew inadvertently entered a stall from which they failed to recover. The Airbus A330-200 crashed into the ocean killing all 228 people on board.

In 1996, 189 people died when Birgenair KT301 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean after taking off from Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic. After a period of maintenance, wasps had made the Boeing 757-200’s pitot tubes their home. The aircraft crashed after the crew lost control while fighting simultaneous overspeed and stall warnings.

It would be just eight months until it happened again, in almost identical circumstances in Lima, Peru. On 2nd October 1996, Aueroperú flight PL603, also a Boeing 757-200, crashed into the Pacific Ocean 25 minutes after take-off. Investigators discovered that maintenance workers failed to remove protective covers on the flight sensors. The crash claimed the lives of all 70 people on board.

Matt is a Berlin-based writer and reporter for International Flight Network. Originally from London, he has been involved in aviation from a very young age and has a particular focus on aircraft safety, accidents and technical details.